Choose Between These Cute Animal Pictures And We'll Predict ...

How The Community Helped Eradicate A Predatory Chameleon Years Ago

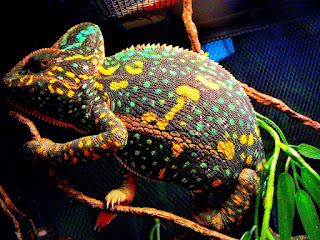

A small population of veiled chameleons was first found by alert Maui residents in the early 2000s. Thanks to community support, these lizards have been eliminated from Maui, protecting native species. — Photo courtesy MISC

High on the slopes of Haleakala are some of the last remaining pockets of habitat for Hawaii's endangered forest birds. The forest here is isolated, and cool temperatures slow the development of diseases that prove fatal to forest birds at lower elevations. Even in this refuge, invasive predators roam the forest: rats, cats and mongoose. These predators, all introduced in the last 400 years, find an easy meal in the eggs and nests of birds that evolved over millions of years without tree-climbing predators.

In the early 2000s, community cooperation kept a new threat from reaching forest bird refuges. Alert and concerned Maui residents worked alongside a multiagency contingent of invasive species professionals to stop the predatory veiled chameleon from reaching upper-elevation forests.

It started with the first sighting of the slow-moving lizard. In 2002, a coffee farmer in Kaanapali found an unusually large chameleon in the fields. It was dead, but he hadn't seen anything like it before and reported the finding to the Hawaii Department of Agriculture. The large lizard was a veiled chameleon — sold in the pet trade but, until this finding, no one thought it had made its home in Hawaii. The Maui Invasive Species Committee launched a campaign to alert residents to the presence of this lizard, hoping that if other chameleons were there, they could be found.

Veiled chameleons are one of 200 species of chameleons in the world, none of which are represented in the native fauna of the islands. This detection would make it the second chameleon species illegally released in Hawaii. The Jackson's chameleon, well known to many, has spread throughout many low-elevation, damp environments in Hawaii.

In their native habitat of Yemen and Saudi Arabia, veiled chameleons are both predator and prey. They're omnivorous, eating plants and crickets, caterpillars or small animals; these reptiles then become food for snakes and large birds. But in Hawaii, there are no natural predators to keep them in check. Jackson chameleons are known to eat endangered native snails, but are so widely established that control is no longer possible. Veiled chameleons are much larger — able to take not just snails, but also small birds for lunch or dinner. In addition to potential impacts on native birds, their ability to tolerate colder temperatures alarmed scientists because veiled chameleons could survive in the high-elevation refuges for Hawaii's threatened and endangered forest birds.

MISC's publicity campaign helped find more veiled chameleons. Makawao residents recognized and reported sightings of the chameleon — they had the same lizard in their own yards. The Hawaii Department of Agriculture, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources and MISC worked with the community to search backyards every six weeks. When people in the neighborhood found the lizards, they turned them in.

By 2003, search crews and residents had captured a total of 102 chameleons. Over time, the numbers steadily declined. The last capture was in 2008.

In 2012, after a final search and outreach to the community, the agencies involved in the effort agreed: veiled chameleons had been eradicated from all known locations on Maui. Addressing the threat early, with community cooperation, prevented this species' spread and protected threatened and endangered species.

While all signs indicate that veiled chameleons are eradicated from Maui, there could still be populations on the island. Staying attentive to unusual animals in your backyard can help protect species across the island.

What can you do? Stay alert for the veiled chameleon. They are distinctive, larger than their horned cousins. They sport a "shark fin" head and saw-tooth fringe on their belly. Veiled chameleons and other usual lizards should be reported to the pest hotline online at 643PEST.Org, by phone at 643-PEST (7378) or to MISC at (808) 573-MISC.

Anyone can turn in veiled chameleons or other illegally owned reptiles through the state Department of Agriculture's amnesty program. Learn more about the veiled chameleon at dlnr.Hawaii.Gov/hisc/info/invasive-species-profiles/veiled-chameleon/.

* Lissa Strohecker is the outreach and education specialist for the Maui Invasive Species Committee. She holds a biological sciences degree from Montana State University. Kia'i Moku, "Guarding the Island," is prepared by the Maui Invasive Species Committee to provide information on protecting the island from invasive plants and animals that can threaten the island's environment, economy and quality of life.

Today's breaking news and more in your inbox

Be The Electronic Chameleon

If you want to work with wearables, you have to pay a little more attention to color. It is one thing to have a 3D printer board colored green or purple with lots of different color components onboard. But if it is something people will wear, they are going to be more choosy. [Sdekon] shows us his technique of using Leuco dye to create items that change color electrically. Well, technically, the dye is heat-sensitive, but it is easy to convert electricity to heat. You can see the final result in the video, below.

The electronics here isn't a big deal — just some nichrome wire. But the textile art processes are well worth a read. Using a piece of pantyhose as a silk screen, he uses ModPodge to mask the screen. Then he weaves nichrome wire with regular yarn to create a heatable fabric. Don't have a loom for weaving? No problem. Just make one out of cardboard. There's even a technique called couching, so there's lots of variety in the textile arts used to create the project.

We get that this is just an example, but we'd love to see a more practical use. Maybe a camera and OpenCV could create smart camouflage, for example. We had to wonder how big you could make RGB "pixels" and still have some effective use as a crude display.

Adding this to OLED-impregnated fabric could be interesting. If you want to know more about using sewing in projects, we have just the post for you.

With Invasive Species, Flattening Curve Requires Cooperation

The veiled chameleon, recognizable by its shark-fin-shaped head, is thought to be eradicated from Maui, thanks to widespread community cooperation and a commitment to seeing the effort to the end. — Maui Invasive Species Committee

In 2002, an unusually large and strange looking chameleon turned up in a remote area of West Maui. The resulting media attention led to the detection of a population of the same species in Makawao. These lizards weren't the familiar Jackson's chameleons, but a new and different species: veiled chameleons. Native to Yemen and Saudi Arabia, these invaders posed a threat to our endemic forest birds and snails. Staff from the Maui Invasive Species Committee (MISC), state Department of Agriculture and Department of Land and Natural Resources launched nighttime surveys, scouring the vegetation in the backyards of Makawao looking for these cryptic reptiles.

During initial searches, the teams found chameleons easily: they were distinctive, larger than their horned cousins and sporting a "shark fin" head, and clung to tree branches as they slept. The community helped by allowing searchers into their backyards and by finding and turning in chameleons on their own.

In 2003, search crews and residents captured a total of 102 lizards, but over time, the numbers steadily declined. From multiple chameleons per night, searchers started to find only one or two per week. Then came months when crews came back from a week of searching without finding a single chameleon. Searchers counted Jackson's chameleons to stay focused on their task. As numbers continued to drop, the time between searches increased. The last capture was in 2008. In 2012, after a final search and outreach to the community, the agencies agreed: veiled chameleons had been eradicated from all known locations on Maui. Addressing the threat early, with community cooperation, prevented the spread of this species into new locations, including higher-elevation rainforests, the last habitat for our native birds and snails.

The language and processes used to stop an invasive species before it becomes widespread mirror the terms used to address an outbreak of a contagious and serous disease. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread worldwide and social distancing measure were implemented, Jane Mangold, invasive plant specialist at Montana State University, considered the similarities in a monthly blog post that circulated through the invasive species community: "One of the most obvious parallels is the importance of prevention, early detection and rapid response. 'Flattening the curve' has been stated repeatedly by experts keeping us informed about the pandemic; the rationale behind this phrase is that by slowing the spread of the disease, medical providers will have more time and resources to treat those in need, and ultimately save more lives," Mangold said.

Initially, reducing the spread of the chameleons cost a lot: hunters had to spend many hours searching to effectively interrupt the reproductive cycle. So too for COVID-19, after months of social distancing and huge economic impacts, the number of new cases has dropped and the curve has flattened. There are other parallels between controlling the spread of human disease and pests.

Those last few chameleons were likely the most time consuming and expensive to remove, but if they hadn't been captured, the population could have rebounded. Working past the frustration and searcher fatigue to find the few remaining individuals was critical to achieving eradication. While eliminating a small population of lizards is not readily comparable to addressing and suppressing a global health pandemic, similar elements lead to success: widespread cooperation by those affected and diligence and commitment to seeing the effort through the long tail of the curve to a resolution. And of course, for both the chameleon and COVID-19, local reintroduction remains a possibility.

We can all do our part to maintain vigilance. And if you happen to see a strange chameleon with a shark-fin on its head while you are at home, report it to MISC at 573-6472. Veiled chameleons and other illegally owned reptiles can be turned in through the state Department of Agriculture's amnesty program.

Learn more about the veiled chameleon at dlnr.Hawaii.Gov/ hisc/info/invasive-species-profiles/veiled-chameleon/.

* Lissa Strohecker is the public relations and education specialist for the Maui Invasive Species Committee. She holds a biological sciences degree from Montana State University. "Kia'i Moku," "Guarding the Island," is prepared by the Maui Invasive Species Committee to provide information on protecting the island from invasive plants and animals that can threaten the island's environment, economy and quality of life.

Today's breaking news and more in your inbox

Comments

Post a Comment